In the biography of Chicago’s Ella Flagg Young written by her former colleague John McManis, there’s a story from her childhood that anticipates her later interest, as a leader in the nation’s second largest school system, in manual training programs. She was fortunate, she told McManis, at being able to learn about mechanics and applied math at the knee of her father, a noted metalworker who would frequently have his curious daughter accompany him to his place of work.

So, though Young’s writings about the benefits of manual training programs in the schools of her day are not so well-known as those of her colleague John Dewey, they are all infused with her strong belief in the importance of this practical experience. From 1887, when she became a deputy superintendent, until her retirement nearly 30 years later, Young advocated for vocational as well as academic education for all students — so long as it was in accord with her equally strong belief that schools should encourage all students to choose their own path through life, rather than be constrained by the circumstances of their birth.

Listed at right are Young’s known comments on manual training and its value, particularly in secondary schools. Her thoughts on the subject in reports to the Chicago board of education have not yet been compiled.

- “Address to Chicago Women’s Club,” given 1899; excerpt in McManis, Ella Flagg Young, page 82 (see below for full reference).

- Isolation in the School. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1901. (Though Young addresses manual training mainly by implication in this work, its themes throughout are the need for greater cooperation between and among all elements of the school system and education’s role in preparing students for their future as citizens in a democracy.)

- “Handwork and Manual Training,” Educational Bi- Monthly 1, 4 (June 1907).

- “The Proper Articulation of Technical Education within the System of Public Education,” Proceedings and Addresses of the National Education Association, 1907, 1037-1041.

- “Reciprocal Relations between Subject-Matters in Secondary Education,” Educational Bi-Monthly 3, 1 (October 1908): 75-84 (originally an address at Oberlin College, June 19, 1908).

- “The Public High School,” School Review 18, 2 (February 1910): 73-83.

- “New Demands on High Schools,” Journal of Education 72 (November 1910): 453-54.

- “Children Should Have Industrial Education Unless They Go to College,” Journal of Education 74 (November 16, 1911): 514.

- “Educational Notes,” Catholic Educational Review 5 (1913): 161-162.

- “Industrial Training” (McManis referred to this as “Vocational Training for Girls.”) Proceedings and Addresses of the National Education Association, 1915, page 125-127.

- “Los Angeles Schools: Ten Years in Advance of the Times,” Journal of Education 84 (February 24, 1916).

Writings about Young

Young was the subject of my 2005 dissertation; her distinguished career has also been the subject of papers by Jackie Blount, who is working on the definitive biography of Young (she also has a website dedicated to Young under construction). Given below are references to some of the most significant work on Young – two recent articles Blount has written, another written by Ellen Lagemann over 20 years ago, the book by John McManis, and my 2005 dissertation. Also on the list is an unpublished paper I wrote, which indirectly at least led to my interest in manual training programs, particularly as a means to address the ills of urban schools.

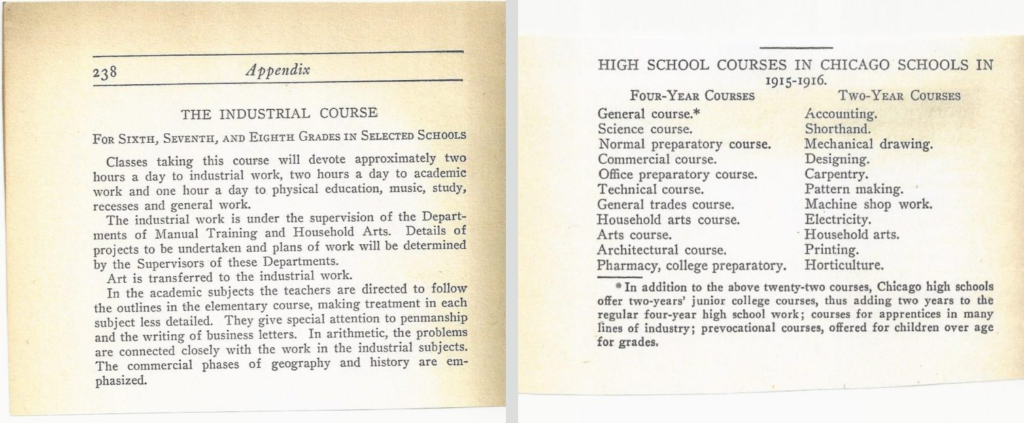

Eventually, this page will include references to manual training programs established in Chicago either by Young (and Dewey) or while she held leadership positions in the Chicago schools.

- Jackie M. Blount, “The Mutual Intellectual Relationship of John Dewey and Ella Flagg Young,” in Antonette Errante, Jackie M. Blount, and Bruce Kimball, eds., Philosophy and History of Education: Diverse Perspectives on Their Value and Relationship (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017); and “Ella Flagg Young and the Gender Politics of Democracy and Education,” Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 16 (2017): 409-423.

- Rosemary Donatelli, “The Contributions of Ella Flagg Young to the Educational Enterprise (Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago, 1971).

- Connie Goddard “Ella Flagg Young’s Intellectual Legacy: Theory and Practice in Chicago’s Schools, 1862-1917 (Ph.D. diss, University of Illinois at Chicago, 2005); and “Democratic Schools for an Isolated Community: Interactions among the Educational Programs of Ella Flagg Young, Booker T. Washington, and W.E.B. Du Bois (unpublished paper, University of Illinois at Chicago, Summer 2003).

- Ellen Condliffe Lagemann, “Experimenting with Education: John Dewey and Ella Flagg Young at the University of Chicago.” American Journal of Education 104, 3 (May 1996): 171-185.

Credits: Picture of Young, from the Chicago History Museum; others from the McManis biography.

- John McManis,. Ella Flagg Young and a Half-Century of the Chicago Public Schools. Chicago: A.C. McClurg, 1916. (Of interest is that McClurg, a noted progressive-era publisher and bookstore owner in Chicago, also urged W.E.B. Du Bois to compile the essays that appeared in 1903 as The Souls of Black Folk.)

- Jane Dewey, “Biography of John Dewey,” in Paul Arthur Schilpp and Lewis Edward Hahn, eds., The Philosophy of John Dewey. LaSalle, IL: Open Court Publishing Company, reprint 1970. (In this piece, Dewey wrote about her father’s reliance on Young for her ability to make concrete through her experience his ideas about schooling.)

- John Dewey, “Significance of the School of Education, Elementary School Teacher 4 (1904): 441-453; also Middle Works 3: 273-284. (In this paper, Dewey described the relationship among the several K-12 schools for which he was responsible in his last two years at the University of Chicago; it included the Chicago Manual Training School.)

- Joan K. Smith, Ella Flagg Young: Portrait of a Leader. Ames, IA: Educational Studies Press, 1976.